Banquet of Knowledge Metaphor

- Elaine Joy Degale

- May 9, 2022

- 10 min read

By: Elaine Degale

Imagine each soul is a colorful star in the classroom emanating its own brilliant light in the co-construction of knowledge around a subject matter. The educator sets the table, and presents the knowledge and subject matter as the feast. And in this intellectual banquet of knowledge in the learning space, students should have permission to eat anything they want so long as they behave with kindness, sincerity and good manners.

The permission to shed one’s light into the buffet doesn’t have to be rigidly limited to one small corner offered up to the student in a bordered space marked by the table cards of their social position. Discourse is non linear and dynamic; it is as fluid in its movement and exchange as the air we breathe. All souls must be free to shine their light, while journeying through their areas of intellectual expertise and unique sensibilities with loving enthusiasm, epistemic responsibility, and well-curated respect for themselves and the world around them. And in this togetherness, learners should not be forcefully subjected to the paroxysm and worldview of the “host” — the educator.

Understanding an increasingly complex world requires nuance, and all souls in the space of learning is not subjected to the proclivities of the educator to pass them the “butter of nuances’’ — especially if a learner’s proximity and familiarity with the “butter” can serve as a better frame for understanding the dense material. This is most important when one learner’s curiosity for this “butter of nuance” is the lived experience of their peers, of which the educator has only read about in books. To enter a social justice discussion with the assumption that the “host” — the educator — is the expert of all struggles that affect every human being on earth is a path to intellectual tyranny. The cyclical nature of discourse and dialogue is never unidirectional, nor should it ever be in service of an exclusionary authoritative agenda. The social authority in the learning space is sensitive to the developmental stages, capacities, and moral values of all persons feasting on the intellectual spread of academic material.

The idea of the students as a collective in a learning space does not mean their unique voices must be painted in one brush stroke, quite the opposite. Their epistemological value - their ”butter”- in a learning space should also be acknowledged in a respectful way without the social constructions that corrupt these voices. But the centrality of differences (be it in our roles, social status, place of origin) should not prevent the teacher from learning from the students. This practice allows the educator to sincerely view their students as contributors, with various personalities, character traits, dispositions.

Students are the Stars of the Show: Educators are the Stagehands

A progressive teacher is an open and humble interlocutor tasked with the responsibility of directivity. They are guardians that mediate instances of power imbalances among students when respect and kindness is being disrupted, when voices are being pushed to the periphery and being eclipsed in a mean-spirited fashion. Disciplined in the art of moderation and humility, educators are tasked with moral discernment in the teaching of human rights that allows everyone a seat at the table of power.

Stagehands set up the tables, chairs, lights, fixtures, and create the well-curated comfort of learning spaces. Educators as stagehands understand that the learners at the seat of the table are the stars of the production of learning. So who writes the script? Paulo Freire suggests that unlike animals who can only marvel at the beauty and tragedies of life’s journey, human reasoning and talent has the capacity to intervene, create, and influence the course of history. There is a neglectful tradition in our current spaces of learning that reduces student value to animals boarding Noah’s Ark - to be paired off and organized into categories that only makes sense to the educator alone. Sometimes there is an expectation that students must ask for permission to have ideas and defend their worldviews. The assumption that a student must ask for permission to participate in their own learning is not aligned with democratic pedagogy, and does not adequately fulfil human rights’ intended pedagogical impact.

The most impactful way that everlasting pedagogy is taught to learners is a type of pedagogy that is not just theoretically hands-on, but is genuinely open to co-construction. Not just in the practice of pedagogical discourse, but even from the creation of the syllabus itself. So why not trust the students to participate in writing the script of knowledge production? Why not trust that students have the human capacity and reasoning to impact the way a syllabus has been traditionally constructed? The stars of the show in today’s world have access to technologies and social media artifacts that may be estranged to us due to the proliferation of many technological platforms. You never know, maybe their adlibs can improve the ways we teach future iterations of the course in the future!

The Everlasting Dream: Is the Legacy of Human Rights a Bonsai or an Oak Tree?

Bonsais are mini replicas of grand trees and lavish greenery. The roots of these small potted plants are restricted to the small area of soil encapsulated by a tiny pot. Unlike the foundations of a flourishing tree that grows deeply into the ground, the roots of a bonsai are confined to the spatial strictures of its tiny box home. Its roots are physically incapable to grow firm and take hold beyond the small pot. While the Bonsai is valued for its pretty miniature beauty and portability, only a tree will have a better chance of surviving a hurricane.

When we think of the way we want to instill moral values in our students, do we want the roots of their moral principles embedded in them like a Bonsai or a healthy Oak Tree? Do we want learners firmly rooted in the values and philosophies of human rights in a way that is timeless, fearless and deeply immovable in their dreams of equality? Are we invested in minds of firm moral roots, forever equipped to brave the winds of conquests that ripple through our global consciousness? Certainly, you would want to plant trees of Peace and Moral Soundness as firmly grounded like the Oak Tree in students today to ensure that the winds of fatalist ideologies will never uproot the foundations of progress for the future generation of scholars. Only a person firmly rooted in the good nature of human beings, as opposed to building hollow brick houses of reason, will be most valuable in grappling with the challenges of the future. When we teach social justice, are we doing it for a Bonsai on our resumes, or are we here for the learners? As educators, we must engage in the task of cultivating a forest of wisdom in our public consciousness to ensure our future generation of scholars are well equipped to grapple with the humanitarian challenges of the future.

Accepting categorizations of human beings without grappling with the nuances of a person’s lived experiences falls short of intelligence. Intelligence is the capacity to see oneself in another person’s shoes and understand the implications your actions may have on the humanity of others. A blind subscription to categorization of people is not only a sign of complacency in the midst of oppression, it is also operating outside of the realms of human rights values. There is no progress in complacency, in the same way that there are no dreams in a perception that accepts fatality and categorizations of human beings as unquestioned truths. Categorizing humans in boxes they were not designed for, is similar to the predicament of a Bonsai plant. When we categorize students without their consent, it subjects learners to a small box that curtails their opportunities to grow into a healthy Oak Tree because we’ve wrongly objectified their humanity by drawing boundaries. How is this different from the Berlin Conference in 1884 when powerful countries took it upon themselves to draw boundaries of ownership on Africa’s resources without honoring human dignity in the legendary “Scramble for Africa”?

The spirit of human rights philosophical principles is firmly rooted in the idea that all human beings are the same. There is no understanding without discourse, and there is no respect without trust. And in a space of growth that curtails any lines of questioning with disdain, has rendered the act of learning and discovery as null in service of someone else’s authority. There are no morals or ethics in a space devoted to alienating inconvenient perceptions. Indifference to a student’s artistic efflorescence and political musings reduces the imagination to silence – an act of intellectual cruelty.

The challenge, then, for educators is: are we still able to love when our students reject, or object, to our dreams? Do we have the patience and understanding to grow and broaden our learners' view of the world? Can we accept that this ironic tension between authority and freedom exists not just outside ourselves but also within us. Do we have the humility to accept that the gap between our worldviews and our dreams are vulnerable to the possibilities of recreation, reconception, reevaluation in the process of its display in the table of knowledge where everyone has a right to question, to debate, to discuss? That perhaps there are lessons, perspectives, and wisdom that our co-constructors of knowledge can offer to the table? This, after all, is the magic of learning and being in the world. And as humans we understand that peaceful resolution of difference is a difficult struggle that requires passion, love, patience, persistence, fruitful engagement, and acceptance.

The Challenge for Educators in Peace and Human Rights Education

On Uplifting Dreams and Enacting Global Social Justice

Authority and freedom is in its most complicated form when the stars in the learning place are at a developmental maturity to have already firmly established their views of the world. It is in this space that the task of the educator is to negotiate authority and freedom while entrusting the learners feasting in the banquet of knowledge. And if the worldviews conflict with the educators and their peers, the responsibility to deliver concerns and personal grievances must have a sensitivity to language use.

Any use of language that reduces the participants into preconceived boxes is the first instance when oppression is exercised in a learning space that is meant to be a form of liberation towards the unified dream of equality. It is our duty to enter any educational setting with humility by extending a hospitable opportunity for students to showcase their dreams. Perhaps in this regard it is more useful in any social justice class to ask students how they paint the dreams of social justice in their consciousness? What exactly does a world that embodies the aim of social justice look like to learners outside ourselves?

I think these questions may provide deeper insights into the brilliance of learners entering the space as opposed to a question of subject matter interest. To give an example, two students can say I study “race and social justice.” The dream of one student in terms of social justice can be, “I imagine social justice will mean all races are equal” and another student can say “I imagine social justice will mean that all races matter and they only build families and communities with people that look like them first – and everyone else second.” The trouble with this, then, is that in some dreams of social justice, race is accepted in one place as a construction that must be challenged, while the other sees race as a determinant of power and preference for their kind over others.

And if we use this word, social justice, with the assumed understanding that it implies equality, we must also inquire what equality means. Equality is a perfect dream that exists on a moral plane, in our unified consciousness as a non-negotiable condition for the realization of solidarity and the practice of human rights. Yet the reality is that equality, in our individual conceptions, exists in different ways and manifests itself in multiple versions of equality and justice. Does equality mean equal voice, equal chances, equal access on paper? Or does it mean equal freedoms, equal sense of authority, equal justice in our actions? And if one sees the world in pieces -- through the lens of colors, boxes, and social status- how do we reconcile our quest for social justice and equality if we refuse to see the world for its holistic beauty? A world full of nuance and potential. A world devastatingly magical in its awe-inspiring brilliance.

A lot of meaning is lost not only in attaching a single story based on superficial qualities, but a lot of meaning is also lost in complex, specialized language. This also means that we have to be careful with language and try not to use polarizing terms like “other” “disadvantages” “lacking” “disempowered” “epistemicide” “privileged” “Microaggressions” because these terms are most effective in academia as a diagnosis of the conditions of inequality that trouble academe. When we enter into the classroom of young adults and children, we should make a fervent attempt to operate within their language and existing schemas. It is more important to pass on wisdom without creating language barriers that proliferate feelings of exclusion. We must enter the space with the humility to understand that the language we’ve developed in our fields (while effective in our respective fields), should not be enforced on certain demographics who have yet to build the universe of knowledge to understand the phenomena these words signify in our specializations.

George Orwell reminded us that purveyors of truth have a responsibility to work beyond the silos of our professions and ensure that we are producing knowledge written in clear language so that it is accessible to the wider public; this is the only way we can truly make our mark on history. In order to ensure that we are impacting the course of education’s history through teaching human rights in fruitful ways, we are tasked with the epistemological responsibility to keep love, acceptance and objectivity perpetually fashionable. We must take great care to not submit students to the lucrative industry of phobophilia that currently pervades the public consciousness. Every student understands the concepts of dreams, love, collaboration, diligence, morality, and hope. So why not start the discourse of human rights at a human level we can all understand in a way that proliferates hope and inspires dreams?

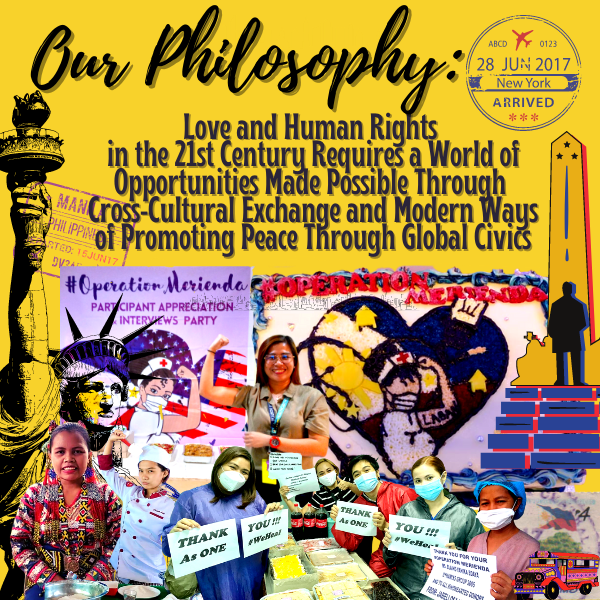

This is why I started Operation Merienda because food is a universal language of love and community building. Merienda roughly translates to "snack" - but in action really means snacking together. If you recall, the history of the Black Power Movement which led the initiative of feeding students free breakfast in the community, stirred the US government into spending federal dollars on free breakfast and reduced lunch programs that exist in our public school systems today. At the time, the Free Breakfast for School Children was so politicized that this form of goodwill was marketed by racist ideology as a threat to American democracy in the late 60s. Similarly, we also observe how Chinese food was also politicized as tainted by racist ideology during the height of the global pandemic. On a philosophical level, the idea of Operation Merienda is to question the narrative of chaos and war that attempts to pit us against each other. Putin may call his war a "Special Operation", but there is nothing special about war's cruelty. What is truly special in this world are the things that spread love, joy, truth, beauty, and goodness. This idea of using food to foster a global community may be our wildest dreams here in Operation Merienda, but it's a scrumptious start towards achieving something really special.

Comments